Rethinking Jobs and Leadership for the Post-COVID World

Common misconceptions mean that companies fail to meet the challenge

Companies need to adapt to rapid change. Globalisation, climate change, technological innovation and a changing workforce all add up to an increasingly volatile and unpredictable business climate. Adaptability and, not least, the ability to reinvent products, services and processes on an almost continuous basis are becoming essential prerequisites for survival. And that’s before we even begin to consider the impacts of Brexit and COVID-19.

We’ve argued throughout the current crisis that it provides a unique opportunity to position companies for the future. But in practice too few companies are actually rethinking the way people work and collaborate. Too few companies are remodelling their internal organisation to tap into and to develop all of the capacities of all of their employees. Less than 20% of UK workers are in jobs that use and develop all of their ability to learn, solve problems, innovate and adapt. In short, we’re squandering the most important resource that we have to survive and thrive in the post-COVID world – human potential.

Misconceptions

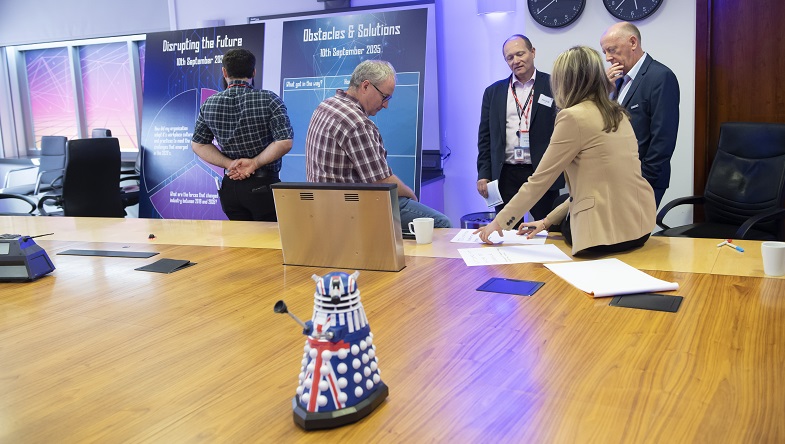

We talk to a lot of companies. Few of them are complacent and most are doing something to address a perceived need to work differently. Yet it is often hard to see how their actions match up to the scale of the challenges (and opportunities) that lie ahead.

We’re grateful to our friend Professor Frank Pot for reminding us of the three misconceptions that recur time and again:

Firstly, there is a common misunderstanding that programmes to train managers in participative styles of leadership represent a sufficient solution. Whilst it may look good to be seen to be doing something about poor leadership or dysfunctional workplace cultures, the decision latitude of managers and consequently their ability to champion employee empowerment participation is determined by organisational structures and systems of governance that can embody very different values and assumptions. It makes no sense to train managers in participative leadership and send them back to hierarchical organisations.

The second misconception is that a happy employee is a productive and innovative employee. ‘Employee satisfaction’ measures, on the whole, the level of adjustment to existing circumstances and not the work environment itself. Being happy with your work may reflect having nice colleagues, a good holiday allowance or workplace perks such as free coffee; however it does not directly enhance individual or group performance. A substantial body of research shows that high performance and capacity for innovation is achieved through individual autonomy, learning on the job, self-managed teamworking, opportunities for innovation and employee voice in ways that harness the tacit knowledge, creativity and commitment of people at every level of the organisation. These practices – known as ‘workplace innovation’ – are exactly those that create intrinsic job satisfaction and reduce psychological stress risks through ‘prevention at source’.

The third misconception is that technology is the answer. Advances in automation, digitisation and advanced manufacturing represent enormous opportunities for both employers and employees. Yet we have plenty of evidence that companies only achieve a sustainable return on investment when technologies enhance – rather than replace – workforce skills. The challenge is to achieve the best possible synergies between digital potential and human potential, embedding workplace innovation in the very DNA of the organisation.