Skills, skills, skills!!?

Frank Pot

Frank Pot

Senior Research Fellow, TNO

A narrow debate

“Skills, skills, skills…” You can read and hear it everywhere. It sounds like a popular Eurovision song. And it’s a very serious song. At the ‘Skills for industry conference’ in June 2019 Joost Korte, Director General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion at the European Commission stressed that “Europe needs a skills revolution. Social partners are crucial. Investing in skills development at all stages of life will be essential to leave nobody behind and to make sure we have the skills that will drive innovation and competitiveness.” This is an interesting broad view. However, in many policy discussions on skills this view is being narrowed to the need for digital skills, the modernisation of formal education and the individual’s responsibility for his or her employability.

In my opinion, that does not take us much further.

Underutilisation

Of course there is a skills gap regarding new technologies that should be addressed. But that’s not the only mismatch. Cedefop’s ‘European skills and jobs survey’ (ESJS) shows that in 2014 about 39% of EU employees had skills that were not being fully used in their jobs, and so did not have potential to develop their skills further. The jobs of overskilled workers typically entailed a low level of task complexity and were lacking adequate learning opportunities. Recent German research shows that new technologies do not change this situation, and new forms of repetitive work emerge (Ittermann & Virgillito, 2019).

The European Commission concludes that overqualification is on the rise and underqualification is declining (European Commission, 2019). Rodrik and Sabel argued recently that the shortfall in ‘good jobs’ can be viewed as a massive market failure – a kind of gross economic malfunction, and not just a source of inequality and economic exclusion. They make the case that this problem cannot be dealt with standard regulatory instruments. Binding agreements between companies, social partners and governments are necessary to start a ’good jobs’ industrial policy.

‘Soft skills’

The next issue is the mismatch regarding so called ‘soft skills’ such as flexibility, intrapreneurship, ability to work in a team, creative thinking and problem solving. This is being emphasised in many statements, but its implications are not very well understood. The most important implication is that organisations should be structured in such a way that they enhance the development of these ‘soft skills’ and are able to benefit from them.

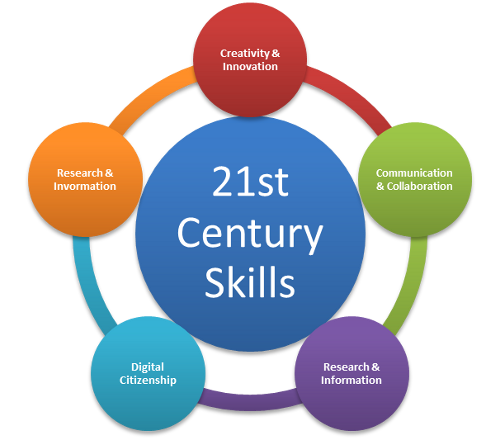

Imagine the many traditional, hierarchical organisations having jobs with little decision latitude or even repetitive tasks, and a ‘command & control’ management regime. In such organisations intrapreneurial workers will be disappointed soon, and the organisation might harvest problems instead of solutions. ‘Soft skills’ and digital skills together are sometimes called ‘21st century skills’. The conclusion of this paragraph seems to be easy: only 21st century organisations with a ‘participation & trust’ management regime can develop 21st century skills and benefit from them. We also know from the research of Felstead and colleagues that a rise in employee involvement induces a rise in skill levels and vice versa.

On the job learning

The policy debate on skills often focuses on formal education, in particular vocational education and training (VET). Formal education should be modernised, teaching 21st century skills and providing lifelong learning. The curriculum should include work-based learning such as apprenticeships. However, this is only half the story. The most important development of skills occurs during working life through informal learning on the job. Creating the best conditions for such continuous learning presupposes a deliberate policy to design high quality jobs with task complexity, job autonomy, skill discretion and organisational participation.

Individual responsibility

Finally, making individuals alone responsible for their employability is not correct from a social science point of view. Of course, individual capabilities and attitudes matter. But individual employability is also related to the work environment as well as to the employment relationship. High quality jobs provide a learning environment. ‘Older’ workers can still acquire new skills if they have been working in a learning environment during their career. The same holds for the employment relationship.

Sometimes workers take the wrong decisions themselves in their careers, but they are to a large extent dependent on bosses and employers for the development of skills and for the sustainability of their employability. One example is that temporary jobs quite often require fewer skills and offer fewer learning opportunities than permanent jobs. Making individual workers fully responsible for their employability seems to reflect mainly neo-liberal ideology.

Conclusion

Developing skills that bring competitive advantage requires investment in training, but also the design of good jobs that can enhance people’s skills and provide wellbeing at work. “Organisations have a significant degree of control in crafting autonomous and learning-intensive jobs, which use and cultivate workers’ skills better,” say Konstantinos Pouliakas and Giovanni Russo, Cedefop experts who designed the skills and jobs survey. It is an important intangible asset and an element of what OECD calls ‘Knowledge-Based Capital’, increasingly considered the foundation of modern economies.

Briefly this means: Every policy regarding skills should also include workplace innovation.

Cedefop (2018). Insights into skill shortages and skill mismatch. Learning from Cedefop’s European skills and jobs survey. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Commission (2019). Skills mismatch and productivity in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Felstead, A., Gallie, D., Green, F., & Henseke, G. (2016). The determinants of skills use and work pressure: A longitudinal analysis. Economic and Industrial Democracy · July 2016, 1 – 25.

Ittermann, P., & Virgillito, A. (2019). Einfacharbeit und Digitalisierung im Spiegel der Statistik. In: Hirsch – Kreinsen, H., Ittermann, P., & Falkenberg, J. (Hrsg.). Szenarien digitalisierter Einfacharbeit (pp. 69 – 86). Broschiert: Nomos.

OECD (2013). New sources of growth: knowledge-based capital – key analyses and policy conclusions – synthesis report. Paris: OECD.

Rodrik, D., & Sabel, C.F. (2019). Building a good jobs economy. Cambridge, MA/New York: Harvard Kennedy School/Columbia Law School (Working Paper, April 2019).

Share This Story!

European Workplace Innovation Network (EUWIN)

EUWIN was established by the European Commission in 2013 and is now entirely supported by contributions from an international network of partners co-ordinated by HIVA (University of Leuven). EUWIN also functions as a network partner for the H2020 Beyond4.0 project.

Contact: Workplace Innovation Europe CLG (contact@workplaceinnovation.eu).