The positive employment impact of Finland’s Liideri programme

Steven Dhondt

Steven Dhondt

TNO

A positive investment decision

Should countries invest in programmes that support Workplace Innovation in firms? The short answer is yes. There is a positive bottom-line for countries that make these investments in improving workplaces or organisational innovation. A well-considered investment repays itself in a short period.

And we understand that you, as reader, need the longer answer to be entirely convinced. We are focusing in this article on the Finnish Liideri programme’s impacts on the stimulation of firm performance and ‘Joy at work’. Let us take you through a set of questions to show what kind of impact such a programme as Liideri have had. Several questions help in our quest: what was the aim of this programme? What impact can we see? How do we assess the final results? Why do we think this is a significant result? And finally, can we explain why such a programme has the impact that anyone interested in workplace innovation would love to see.

The Liideri programme in a shifting context

Our short answer is a bold statement. We derive this answer from reading the evaluation report on the completed Finnish Liideri programme (full name: Liideri, Business, Productivity and Joy at Work Programme 2012-2018) (Business Finland, 2019; Oosi et al., 2020). Next to the fact that our Finnish colleagues are great programme managers, they also have the good practice to evaluate what they have been doing.

The Liideri programme started, in fact, under the guidance of the TEKES programme, a Ministry of Employment and the Economy initiative. All such programmes were refocused in 2016 as part of the change in strategy of TEKES. In 2018 Business Finland was made responsible for the finalisation of the programmes. Besides the Liideri programme, there were also the Feelings (Creative Industry), the Luovimo and the Lifestyle programmes. The latter two mainly aimed at deploying external expert support for firms. The financial scope of these two programmes was also much smaller than Liideri and Feelings.

For TEKES and Business Finland, Liideri and Feelings were unusual initiatives in that their focus was on intangible innovation, and their approach was somewhat human-centric. TEKES and Business Finland are mainly focused on innovation financing and export support for firms. Business Finland positioned these new programmes as awareness-raising campaigns focused on the importance of non-technological innovation.

‘Liideri’ stands for Leadership. It focuses on leadership in business, productivity and joy at work. The Liiderii programme started in 2012 and was finalised in 2018. At the start of the programme, the actions were very much in line with the previous (TYKES) quality of work programmes that the Ministry of Labour and TEKES have managed, implementing the Working Life development strategy of the Finnish government.

In 2015 and 2016, the programme changed in mission and vision. The purpose of Liideri was to be a “next-generation” workplace innovation development programme that represents an approach in keeping with a broad-based innovation policy, i.e., the new Finnish national innovation strategy adopted in 2008 (Alasoini, 2021). After that change, the programme focused on international growth and digitalisation. The impact of Business Finland on the Liideri programme can only have been limited since it just took over the governance of the programme in 2018, at the end of the programme. The shifts over the years came in the changes in what TEKES tried to achieve with new themes such as participation, new working methods, managing international growth, and utilising digital technologies. The shift in strategy to international growth meant that only firms that looked at growth in the international markets were included in the programme. For the topic of workplace innovation, this may at first seem to be a limitation. Still, understanding how quality of work and productivity are connected is even more interesting. Liideri provides (some) information about the effectiveness of such a programme for international development and growth. There was nonetheless concern about this redirection in the Finnish context because public institutions and firms focused on growth in the Finnish market were left out.

The view from the evaluators

According to the evaluators, Liideri has recorded many concrete results at project level. The development projects led to some important (organisational) changes for participating firms, and pushed them along their development path. The evaluators also point out that the final adjustment of the programmes did not happen automatically. The adjustment in focus was accompanied by a decision only to allow export-oriented companies to get funding and to raise the bar for large companies. These decisions led to a decrease in the number of project applications. Somewhat euphemistically, the comment is that adaptation required careful planning and communication with programme participants.

The evaluation report by the Owal Group & MDI (Oosi et al., 2020) is intriguing. It analyses the results for four major programmes by comparing the performance of firms funded by the programmes with unfunded control firms. Liideri is only one programme in this evaluation. The report provides numbers and assessments of these numbers. For Liideri, the assessment is that there was too little data available to make a full evaluation – the impact of the programme will only be visible three years after the project decision.

Nevertheless, there are results to be seen. The Liideri firms show faster growth in turnover than the control firms, a statistically significant result for all firms and new customers of Business Finland. The growth in the number of employees has been faster in the Liideri firms compared to the control firms. Interestingly, the development in added value per person has been similar between Liideri and the control firms. Programmes such as Liideri always lead to an increase in costs at the outset. The fact that productivity did not decrease is certainly a positive message for the programme. The evaluators make the results more tangible by indicating that in 57 to 58 out of 100 cases, a funded firm grows faster than randomly selected control firms. The corresponding effect size is 61 to 62 among firms that are new customers (i.e. firms that have not received previous funding from Business Finland). Liideri would not affect the firms’ export performance.

Does one wonder if this was the original expectation then? Before the strategy change in 2016 and the actual implementation, the programme was mainly focused on the internal development of staff and organisation within the participating companies. These companies were focused on growth, probably mainly in Finland. Only at the end of the programme, the international impact was introduced as a goal. Apart from the fact that this focus is difficult to trace, it is also a bit “too little, too late”. Besides, the impact of the last cohorts, in particular, is not yet visible.

Still, the report itself is not very conclusive on the impact of the Liideri programme itself. Probably the authors wanted to err on the side of caution. That is, of course, wise, but it does leave out positive messages that should be shared. The evaluation perspective is also exclusively on individual firm benefits. What is not discussed is whether the programme itself shows a positive return on investment? Can we estimate whether the policymakers’ investment has generated a positive return?

What about the societal benefits of the programme itself?

The results do help us to calculate this ROI. The programme eventually reached 267 firms. On average, these participating firms employed at least 50 persons. Our Finnish contacts indicated that the average size of the firms was actually bigger. This meant that the firms employed at least 13.500 employees at the start of the interventions.

The evaluators first show that the Liideri firms have a 10% higher turnover growth than the control firms after three years. This difference persists two years after the programme. For evaluation purposes, the number of firms dropped for ‘two years after project closing’. The actual number was too small to deliver sounding results. Even so, the figures do deviate in the right direction. Most of the evaluation is focused on the investment period plus three years after finalising the separate projects. We can expect that there may be a ‘petering out effect’ after the discontinuation: so without further investment, the impact of the initial investment should be lower. This is, however, the pessimistic scenario because, with workplace innovation, this should be a permanent impact (Gibbons & Henderson, 2013). The Feelings programme shows results in line with Liideri, but the statistical underpinning of positive results is less decisive for these firms. The Liideri firms always compare better than the control firms, whatever indicator is used. These results can be seen as positive breadcrumbs for supporting programmes, but important ones for any discussion about the economic impacts.

The employment effect is also 10% above the control firms. For any person interested in workplace innovation, this is certainly an issue that should draw attention. What does this employment effect mean? Could we assume that implementing such a programme leads to a 10% higher growth in employment? Maybe. Suppose we concede that the result might be less than 10%, mainly because of the low statistical significance of results. In that case, we can assume that we should not use a 10% difference with control firms, but maybe only a 2-4% jobs growth difference to estimate the impact of this result. A simple calculation shows that with the 13.500 employees x 0,02 to 0,10 = 270 to 1350 new employees after 3 years. The figures seem to hold after two years, closing of the project. What do 270 to 1350 new employees mean? Can we get a feeling of what this represents in added value for society? And how does this relate to the initial investment by Business Finland?

If we assume that the average yearly wage cost for a Finnish employee is €40.000, this will mean that in year 3, we see an additional wage cost between € 10,8 million to 54 million a year. We are not completely sure what happens after three years, but it seems that the impact persists, so: 10,8 to 54 million for at least three years = €32,4 million to 162 million in total (above control firms). Let us do this in a more precise calculation.

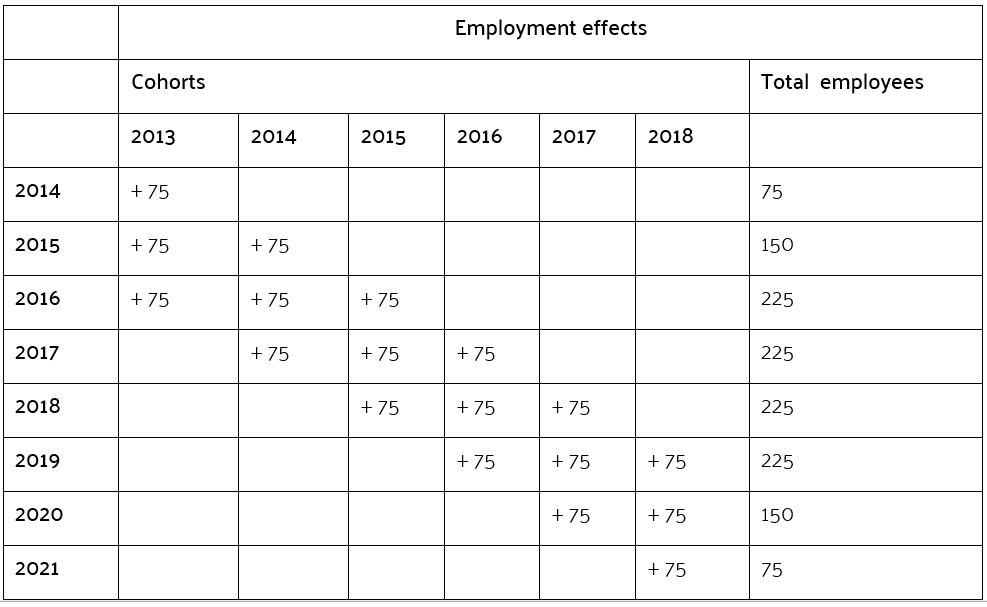

Let’s assume that the total investment of €126,3 million is split evenly during six years of operation (2013-18), which means that the annual investment is €21 million. Let’s also assume that the participation of firms is split evenly during six years of operation, which means that every year new firms with 2250 employees are funded. If the programme starts project funding in the year 2013 and it funds firms with 2250 employees, the extra employment growth in 2014 is 75 employees. Table 1 shows how this works out.

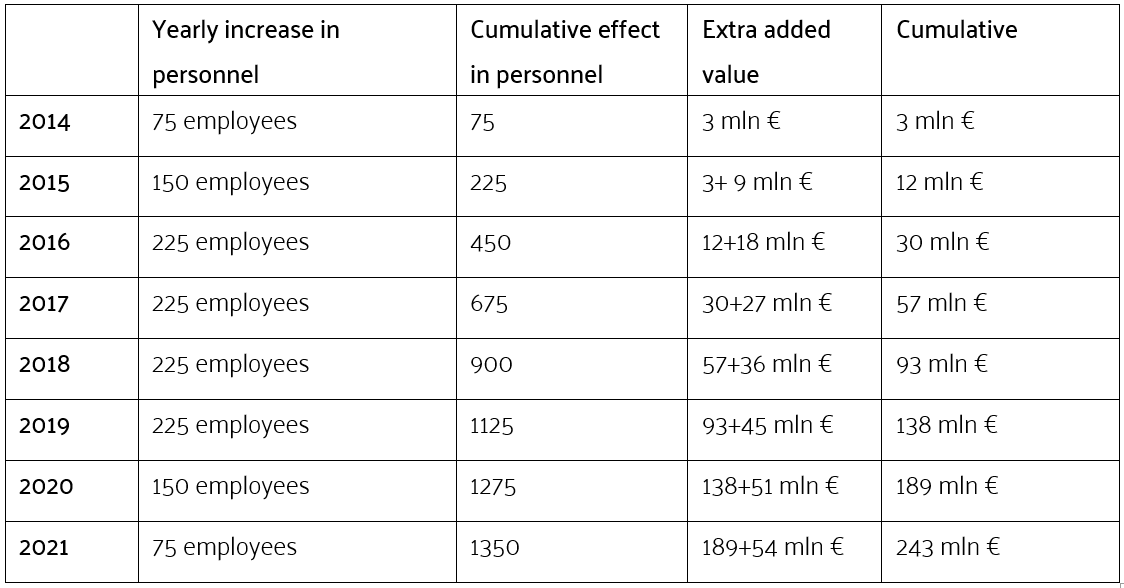

After 2021 there is no extra growth. With our assumption of an average wage cost of €40,000, the added value by the programme accumulates as seen in Table 2.

Calculated in this way, the added value by the programme exceeds the level of investment during 2019. Of course, the calculation misses the point that the programme’s value is dynamic and cumulates only in time. This positive cumulative trend also presupposes that the involved firms continue their development after the end of their project, and they managed to maintain the competitive edge they have gained. Still, by the end of the programme, it has paid for itself, and after eight years, it has nearly doubled the initial investment.

Why are these outcomes significant?

There is little evidence in the scientific literature of the actual benefits for firms and societies of such workplace innovation projects. The final presentation and the evaluation report of Liideri provide anecdotal evidence of the impact of the intervention. It is not completely clear what the firms have done to change working procedures and what this has meant for employees. The figures show both abstract performance benefits. It would be good to understand what the other benefits are. In most evaluation studies, the stress is on the qualitative impacts such as quality of work, stakeholders’ satisfaction, and the actual changes in the firms (Alasoini, 2016; Pot et al., 2021). This evaluation report does not pay any attention to these qualitative results. These results will not be documented in future publications, as far as is known. Such evaluations are, however, needed. Practitioners will want to understand what they need to change and what they may see as actual processes after interventions.

The fact that the evaluation of the Liideri programme shows a positive employment effect is significant. If only the firms’ performance improved, then the public investment would merely have been a tax transfer to the firms. Public money would have lowered the tax burden and improved performance. It could even be the case that Finnish tax funds could be exported, depending on if the firms had international management or ownership. The employment effect is really a local impact. These employment benefits are for the Finns and the local economy. The fact that the export performance of the firms improves (well, that is not completely clear) also helps Finland improve itself compared to the rest of the world.

Another result is that the study allows for comparisons between programmes and other public investments. It would be good to see if such organisational improvement programmes have higher societal outcomes than labour market activation programmes.

In conclusion, even with the limited information we have about Liideri, the evaluation results help programme managers develop plans for organisational change. We must remember that most programme managers arguing the importance of such programmes are stuck between a rock and a hard place. They need to argue that such (public) investment will deliver positive outcomes, but they know that actual results will take time (Alasoini, 2021). And in most cases, they don’t have this time. They are pressured to show immediate results. Until this Liideri evaluation, they had no clue when such results could arise and how big they may be. The Liiderii programme brings just this kind of insight: you do not have to wait for a long time to win your (public) money back.

Lessons for future programme management?

Developing and implementing a programme for the improvement of organisational structures and systems is complicated and difficult. Rodrik & Sabel (2019) advocate an open programme management approach to such an endeavour in which stakeholder parties are able to monitor and follow activities regularly. The Finnish agencies have been able to develop and evaluate impactful programmes. The Liideri programme is evaluated as a programme with a positive impact. However, the programme’s buzz is limited, and this neglects the actual benefits such a programme has. It is good to understand these benefits and to learn from the programme management that was conducted. The evaluation report only touches the surface.

Oosi et al. (2020) summarise two lessons:

The first lesson in programme management is that changing the management team comes at a cost. Programme managers and staff provide continuity. They have knowledge, networks and experience. Intervening in this leads to disruptions that can only be dealt with in the longer term. It is, therefore, all the more striking what benefits the programme ultimately delivered. The evaluation report also points out that to create impact, another, more eco-systemic approach is probably needed in the end, in which the cohesion between firms is strengthened. The programme management must respond to this cohesion, which clearly requires different competencies and different programme management actions. The guidelines of Rodrik & Sabel are helpful here.

Liideri was a continuation of a long tradition of innovation instruments to develop working life in Finland (Alasoini, 2021). Although there were many success stories for the individual firms at the project level, changes in Tekes’ strategy rendered some of the programme’s original ideas obsolete. The themes presented in the evaluation report do not include those relevant to that programme. Still, based on the findings, it could be argued that support for employer-driven and management innovation is not part of public funding schemes and does not fit into the thematic portfolio of activities of Business Finland and the Ministry of Employment and the Economy. This leads us to ask whether this is something that the Ministry of Labour should consider including in the development of working life and guiding public funding. Organisational innovations should be compared to other labour market activation programmes. Such a lesson is understandable, but what firms do and what impact they may have should not only be on the plate of Labour Ministries. This is the kind of silo-thinking that organisational innovation seeks to address. Another suggestion could be to create inter-ministry cooperation on the different outcomes. The public benefits are important for more policymakers. Also, we must understand that most Labour Ministries have a strong focus on labour market policies and institutions. They are very reluctant to say anything about firm policies. Therefore, a collaboration between Ministries would be a better option.

In the meantime, the Finnish Prime Minister Marin’s government launched a new WORK2000 programme that has now been in operation since the beginning of 2020. This programme is coordinated by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH) under the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health and labour market organisations’ guidance. There is a lot of continuity, but also discontinuations with previous programmes.

In conclusion

Public investments in organisational innovation do lead to positive public benefits. Our assessment is, of course, limited. We surely want access to the data and do more in-depth calculations. We would also need to look at the separate interventions and the impacts on the employees. These last impacts are not visible. At this moment, we only work with the results from the evaluation report. There remain many limitations to our approach. All of this is very true. But still, even if you consider all the limits to what has happened in the programme and what we can see, there is this clear positive bottom-line. It would be professional neglect if we were not to share this insight. Many countries want to understand whether they should invest in improving working conditions, quality of work, and organisational innovation. The European Commission invests many European Social Fund-millions into improvements of workplaces. Guidance on how programmes could be developed to use organisational innovations such as workplace innovation should be on the agenda.

Acknowledgement

A version of this paper will be published in the European Journal of Workplace Innovation.

Alasoini, T. (2016). Workplace development programmes as institutional entrepreneurs: Why they produce change and why they do not (Doctoral Dissertations 12/2016, School of Science, Aalto University, Helsinki).

Alasoini, T. (2021). Evaluation of the Tekes Liideri programme (2012-18). Presentation to EUWIN-workshop 14-3-2021.

Business Finland (2019). Liideri, Business, Productivity and Joy at Work Programme 2012-2018. Insights on leading international growth. Helsinki: Business Finland.

Gibbons, R., & Henderson, R. (2013). What do managers do? Exploring persistent performance differences amond seemingly similar enterprises. Gibbons, R., & Roberts, J. (Eds.). The handbook of organizational economics. Princeton 554 (NJ): Princeton University Press, 680-731.

Oosi, O., Haila, K., Valtakari, M., Eskelinen, J., Mustonen, V., Pitkänen, A., Gheerawo, R. (2020). Evaluation of Programs for Customer Experience, Creative Industries and Human-Centric Business. Evaluation Report. Helsinki: Business Finland.

Rodrik, D., & Sabel, C. F. (2019). Building a Good Jobs Economy. Cambridge, MA/New York: Harvard Kennedy School/Columbia Law School (Working Paper, April 2019).

Share This Story!

European Workplace Innovation Network (EUWIN)

EUWIN was established by the European Commission in 2013 and is now entirely supported by contributions from an international network of partners co-ordinated by HIVA (University of Leuven). EUWIN also functions as a network partner for the H2020 Beyond4.0 project.

Contact: Workplace Innovation Europe CLG (contact@workplaceinnovation.eu).